Workshop November 2019

Yes, we had our first Luftdaten.info workshop. Before we go into the details we have to thank

- Civic Tech Innovation Network (CTIN) for their monetary support of the sensor components, refreshments, and pizza.

- OpenUp and Codebridge Newlands for the organisational support and awesome hackerspace venue.

- All the attendees. What a great, supportive community we have. ❤️

tl;dr

On November 9 we came together to assemble open source outdoor sensors that will produce open data on the air quality in Cape Town. The workshop was a success and proved to be essential in providing support to each other.

Hopefully it can be used as a template, be improved in future iterations, and help further the IoT-based citizen science community in our region.

If you’re interested, feel free to join us on the community mailing list or contact hello@air-cape-town.org.za to sponsor a workshop.

Photo: Kirsten Pearson, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Kirsten Pearson, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Motivation

Visit luftdaten.info or watch this brief video to see what the upstream project is about. Our specific local motivation was to tackle the following challenges:

Assist with component procurement

South African hobbyist hackers and makers know of the difficulties when trying to purchase electronic components. Local distributors don’t have specialty electronics like the SDS011. When ordering from overseas one can either overpay a premium courier like DHL or UPS to handle shipping and customs, or try one’s luck with the SA Postal Service and SARS. The latter usually presenting itself as a 4-6 month kafkaesque endeavour - many shipments ending up lost. Lastly, for novice makers, differentiating the vast variety of components with similar specs can be daunting.

Purchasing as a group is a huge benefit in every aspect.

Citizen science in Africa

With our experience at the hackerspace and civic tech hub Codebridge Newlands we have witnessed that establishing and maintaining volunteer open source projects in Africa bear far more challenges than witnessed in the “Western World”. We are going to use this opportunity to document and share key findings at air-cape-town.org.za on how to grow an IoT-based civic tech project in South Africa.

Moreover, we want to expand the local community, find more sponsors, and make these workshops replicable by others. See Key learnings.

Gather good data

Unfortunately the Department of Environmental Affairs (see station metrics at saaqis.environment.gov.za) has very poor and little data. Admittedly, maintaining physical outdoor sensors is in fact hard work. Although all our attendees were highly motivated, we used the CTIN funding to sponsor the hardware costs and will ask the workshop participants to provide a minimum of 3 months worth of sensor data.

Photo: Kirsten Pearson, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Kirsten Pearson, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Key learnings

The workshop format

Although many could’ve easily managed by themselves at home, it became evident that a dedicated workshop is beneficial in many aspects.

- We all have busy lives. Having a dedicated time and place avoids delays

and distractions.

- Connecting with community members and eliminating inhibitions to ask “stupid” questions.

- Jointly managing obstacles that would otherwise be a possible showstopper.

Venue

Fast internet for accessing instructions, GitHub, and doing research was essential. A local WiFi access point to join and access the sensor readings is imperative, and access to the DHCP leases very valuable.

Space to spread out as well as sufficient seating and tables. Many power plug points for computers, sensors, soldering equipment. Throughout a long session you’ll have to think about bathrooms and space for food and drink.

All of this might appear self-evident, but with a history of African hackathons in libraries, community centres, schools, and warehouses these can become serious obstacles. With OpenUp’s Codebridge and JD Bothma as a host, luckily these aspects were taken care of.

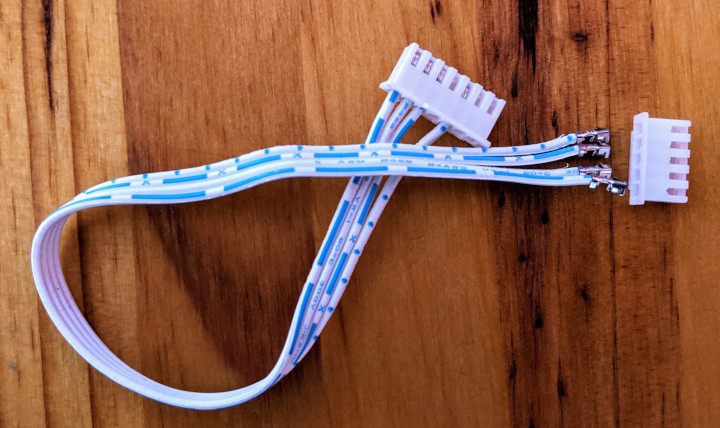

Connectors

In general the sensor build should be toolless. Unfortunately the DuPont jumper cable connectors between the microcontroller (esp8266) and the other components are often flimsy.

Usually the SDS011 comes with an USB serial adapter and we recommend using the manufacturer’s cable for a reliable connection. Additionally, the pins on the DHT22 are very thin, do not hold to jumper connectors, and need to be either soldered or crimped.

Photo: Reuben Honigwachs, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Reuben Honigwachs, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Using electrical tape to isolate the soldered connectors is cumbersome and we recommend adding heat shrink tubing to your shopping list.

Flashing and networking

The “new” firmware

flasher is a

huge help compared to Arduino IDE and esptool. In our case many wanted to

understand the flashing process, i.e. getting the software on to the

microcontroller and adding it to a WiFi network. Unfortunately this means that

you have many ad-hoc SSIDs popping up at once without knowing which is yours.

Once added to the network you’re faced with the problem of identifying the DHCP

IP of your particular sensor. As mentioned above, access to the DHCP lease table

is very helpful, since the MAC addresses and DHCP client name of the esp8266

have the same pattern.

To save time during larger events one could define a “flashing team” that takes care of uploading the firmware to the device, adding it to the network, and labelling the board with ID, MAC, and IP. One by one. Then handing it out to the participants. In a restrictive WiFi environment where the venue’s admin is absent, this team could maintain it’s own Access Point.

But in our case many attendees were technical and wanted to explore this part of the process.

Time management

We planned for 4h and many stayed longer. Our schedule included:

- Morning coffee

- Project overview presentation

- Introductory round

- Build session with pizza in between.

For a larger workshop we’d need to define two dedicated help desks or roles. These would outline pitfalls and caveats at the beginning of the workshop and later purely assist in these areas:

- Software & networking

Experienced community member/s helping out with issues while uploading the firmware, managing WiFi and DHCP. - Hardware

Helping out with electronics and physical aspects of the build.

Luckily we had very supportive community members, some pitching up purely to help. If one had to schedule an evening event over ca. 2h, then the preparation of microcontrollers would be an absolute necessity.

Communication

We made sure to stress the fact that hosting a sensor won’t be as trivial as many might think. Over the past year we faced many issues where the WiFi backhaul wasn’t working, sensors were stolen and vandalised, continuous power supply wasn’t provided. We still have to prove a track record, but this was something we made sure participants were able to guarantee.

Photo: Kirsten Pearson, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Kirsten Pearson, CC-BY-SA 4.0

The way forward

Moah workshops!!

With the success of this event we are convinced workshops are a very useful format to onboard new community members and further the project. We would like to find strong partners that can provide monetary support for the components as well as venues.

Data science projects

All the data we’re producing is publicly accessible via map, archival CSV, and API. Once we have secured and proven a steady and reliable influx of air quality data, we will invite the wider civic tech community in Cape Town to have a look. During the workshop many already had ideas such as localised alerts, correlation of weather data (e.g. the Cape Doctor), and visualisations.

We will be regularly releasing stats and progress reports here at air-cape-town.org.za once all attendee sensors are online.

Reducing costs further

We’ll probably dive into this deeper with another blog post, but if we can reduce the costs further, it would become an even more viable citizen science project for Africa.

- Distributors and shipping costs.

By carefully vetting and selecting both distributors and courier companies we can certainly find a good balance between reliable, timely delivery and costs for shipping and handling. As a South African community we should continuously monitor local distributors and communicate significant changes. - Housing.

Pipe bends make up a significant part of the costs. We can certainly do better by reusing durable plastics (e.g. ice cream containers) and modifying them to the projects standards. BTW, in our case we had to saw up some connector cuffs to join the low cost 75mm bends.

The LoRaWAN challenge

WiFi with internet is far from being omnipresent in Africa, so hosting the esp8266 build with WiFi backhaul is challenging. Also, WiFi is quite power-hungry. LoRa radio is low power and long distance by design. Switching to LoRaWAN, specifically the free and open The Things Network (TTN), would solve both of these issues and make outdoor installations independent from WiFi and a power supply.

We are very fortunate to have an active TTN community and good coverage in the Cape Town Metro area. Already there are many attempts and open source TTN PM builds. Unfortunately these aren’t cheap nor standardised, yet. But we are getting there and will keep you posted.